The 1,000 person march (for theatre)

June 15, 1937. New York City. The Maxine Elliott Theatre.

Marc Blitzstein's new musical, The Cradle Will Rock, is set to open the following night. It's a Federal Theatre Project production, directed by 22-year-old Orson Welles.

But, at 5pm, WPA officials arrive: all FTP openings delayed until July 1. Federal agents lock the doors, impound the sets, and seize the piano.

But if you know anything about theatre people, the show must go on.

Pictured: Marc Blitzstein and cast; 1937.

Dangerous art

Blitzstein's "play in music" told the story of labor organizing in "Steeltown, USA." It was pro-union, anti-capitalist, and unapologetically political.

Weeks earlier, the Memorial Day Massacre saw police open fire on striking steelworkers and their families in Chicago, killing ten and injuring dozens. A musical about workers standing up to corrupt industrialists wasn't just relevant; it was incendiary.

At the same time, the Federal Theatre Project was approaching its congressional funding review. Political allies warned FTP director Hallie Flanagan that proceeding would be "irresponsible,” handing ammunition to critics who already called the project communist propaganda. Letting this show open could jeopardize the entire program.

But Hallie approved the production anyway. She knew there was no safety in prudence…and no virtue in caution.

The shutdown wasn't about budget cuts. Everyone knew it. This was censorship dressed in bureaucracy.

Pictured: Marc Blitzstein rehearsing cast members for the Federal Theatre Project production of The Cradle Will Rock at Maxine Elliott's Theatre

The March

Welles and producer John Houseman refused to accept the show’s abrupt closure. By that evening, they'd secured the Venice Theatre — an abandoned space 20 blocks north on Seventh Avenue.

Word spread through the theatre community. Audience members showed up to find doors chained. Someone announced: "The show's at the Venice Theatre. Let's go." En masse, actors, audience members, and theatre workers walked together up Seventh Avenue. By the time they arrived, nearly 1,000 people had joined.

But Actors' Equity prohibited members from performing without the producers' consent. The government wasn't consenting. If actors took the stage, they risked their careers.

The Performance That Made History

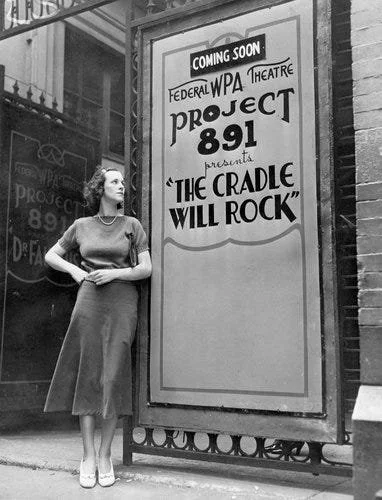

Pictured: Olive Stanton, outside Maxine Elliott’s Theatre, in the summer of 1937.

The solution was brilliantly subversive. Blitzstein would perform alone — piano and vocals, and all parts. Technically, the actors wouldn't be "performing" at all.

The lights went down. Blitzstein sat at an upright piano — the only instrument they'd found — and began to play. Then, from the audience, a voice joined him. Olive Stanton — 19 years old — stood in her seat and sang her part. She wasn't on a stage. She was just an “audience member,” expressing herself.

One by one, actors stood throughout the crowd. The audience watched performers scattered among them, singing this pro-union musical about labor organizing by literally organizing themselves into a new form of theatre.

The fourth wall dissolved. Theatre became community action.

What It Cost

The rogue performance proved everything Hallie believed about theatre's power: that art could be immediate, necessary, and unstoppable. But it also proved her critics' point: the FTP couldn't be controlled. Broadway producers refused to touch the New York unit. Some of Hallie's own artists turned on her, accusing her of complicity in the shutdown.

She was tempted to resign in protest. Instead, she stayed to protect 10,000 artists across 40 states, knowing it would cost her.

"This is a big country," she wrote. "Federal Theatre was bigger than any single project in it."